Will You Drown If You Swim After Eating Ice-Cream?

Do not get fooled by statistical quacks who mislead people using numbers and charts

It is said that advice is a dangerous gift, even from the wise to the wise. And yet, everyday we are flooded with advice that reaches us through newspapers, television, magazines, Facebook feeds, blogs, even marketing pamphlets. We are not only bombarded with unsolicited advice, but we also actively seek it from the web and print media. Entrepreneurs breakfast on management blogs, new mothers are glued to the Internet for advice on how to raise children, and retired executives turn on their favorite finance news channel every morning. Whenever we read something in print (or see it on TV) we assume it must be true without giving it a second thought. Unfortunately, much of it is utter bullshit, occasionally even sheer lies, and often the author herself is a victim of misplaced reasoning. Most pieces of factual news use some sort of statistical evidence to support their claims. Although statistics is invaluable as a tool to convert raw data into information, be aware that it is also a minefield of logical fallacies that we fall prey to a bit too often. Everyone, authors and readers alike, must learn to protect themselves from getting fooled by statistics.

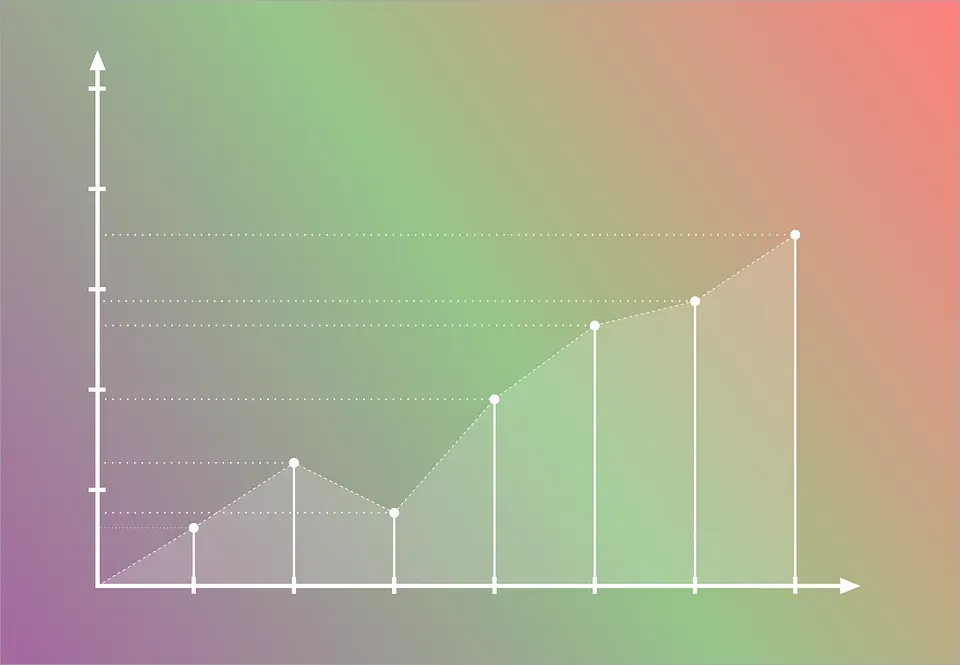

Journalists use statistics all the time to create drama and sensation even where none exists. What happens when a dishonest journalist desperately looking for a new story comes across the following fictitious piece of data regarding potato prices over the past one year?

We can see from the table that there is nothing to be alarmed about. The prices today, in November, are the same they were almost a year ago in January. But don’t be surprised if you read a dramatic piece of news in tomorrow’s newspaper written on the following lines:

POTATO PRICES DOUBLE CAUSING FRUSTRATION AND RAGE

Poor rainfall and short sighted decisions by policy makers have caused potato prices to double in the previous 4 months from Rs 10 per kg in July to Rs 20 per kg in November. The spike in prices has caused an increase in food costs, ahead of crucial assembly polls and general elections in 2014. The increase in the inflation rate both at the retail and wholesale level should come as a fresh policy worry for the government and the central bank which are trying desperately to tame spiralling prices.

While the article above does state objective numbers, it clearly presents an incomplete picture for the sake of telling a story which is not entirely true. Manipulation of data pervades all fields including academics, medical sciences, finance, and marketing. If you have a large enough dataset, it is almost always possible to cherry-pick data so that it leads you to the conclusion you want. Dr. Peter Wilmshurst is a vocal critic of dishonestly and fraud in the medical profession. In an exposing speech that you can read here, he talks about Amrinone, a drug intended for treatment for heart failure. His team conducted experiments on the efficacy of the drug and found it to have severe side effects. The pharmaceutical company that funded the research, Sterling-Winthrop, went to great lengths to prevent these results from going public. They resorted to data manipulation, coercion, legal threats, and even bribery. So next time you read about a study claiming health benefits of green tea, check if it was funded by a tea manufacturer!

There is another tendency, hasty rationalization, which is endemic to journalism, especially scientific and financial journalism. Journalists are trained to report facts. They are not trained to draw inferences and offer explanations. Our world is an extremely complex system where most significant events worth reporting can occur due to multiple possible causes making it difficult to single out a cause. Yet, without considering alternate causes, journalists pick up the first plausible explanation they can find and offer it in such a brash and confident manner that we are left believing that’s exactly what happened. Nassim Taleb, in his eye-opening book Black Swan, gives the following example. After Saddam Hussein was captured, Bloomberg flashed news titled US Treasuries Rise; Hussein Capture May Not Curb Terrorism. An hour later treasuries fell, and Bloomberg flashed US Treasuries Fall; Hussein Capture Boosts Allure of Risky Assets. They attributed the exact same cause — Saddam’s capture — to two opposite events, treasuries rising and then falling. In reality, the rise and fall of treasuries might have had nothing to do with Saddam’s capture. So when you read news, keep in mind that there will be several alternative explanations which the writer might not have considered.

As I was writing this post, I came across the below article freshly published by TIME magazine. The piece titled Why Owning An Inexpensive Kindle Could Cost You Hundreds? demonstrates how naive and fallacious reasoning affects even reputed sources of information like TIME. The article says:

CIRP surveyed 300 U.S.-based Amazon customers over a period of three months this fall. Based on the results, the firm estimates that Kindle owners spend about $1,233 per year on the site, compared with $790 for Amazon members who do not own one. In other words, Amazon members with Kindles spend $443 more annually.

The article correctly states the objective fact that Kindle owners spend more, but the title Why Owning An Inexpensive Kindle Could Cost You Hundreds? wrongly implies that simply owning a Kindle will make its owner spend more. This leap of logic is blasphemous, and the article should never have been published. Successful people wear Rolex doesn’t mean just wearing a Rolex will make you successful. Basketball players are taller than others doesn’t mean playing basketball will make you taller. Similarly, the fact that Kindle owners spend more than others does not mean that owning a Kindle will make you spend more. Such flawed reasoning is commonly found in market research and analytics where data is abundant and people are paid to interpret it and draw conclusions.

The saying goes correlation does not imply causation. Somebody might tell you that they have reliable statistics that, in a particular city, an increase in ice-cream sales causes an increase in drowning deaths. But now we know that the correlation between ice-cream sales and drowning deaths does not imply the causation that ice-cream causes drowning. People eat more ice-cream on warm summer days than on cold winter days. People swim more on warm summer days than on cold winter days. Consequently, both the figures, ice-cream sales and drowning deaths, are higher in summer than in winter. In the real world, the link explaining the correlation is often much more complex than this so people mistakenly attribute the observation to causation. Now, spending habits of Kindle owners may not matter to you, but when such reasoning finds its way into that magazine offering advice on feeding your 6 month old child, you should avoid trusting its claims without due diligence.

Once you start looking for it, you see data manipulation and fallacious reasoning everywhere. But there is a deeper problem called publication bias that plagues academic research and is much more dangerous and difficult to overcome. The research community has a bias towards publishing positive findings and discarding negative ones. Imagine that you are a researcher investigating whether drinking coffee increases your likelihood of catching flu. You call in a group of subjects and divide them into two groups. You serve coffee to one of the groups and just plain water to the other. A week later you find that the incidence of flu was roughly similar in both the groups so you conclude that there is no evidence linking coffee consumption to flu. You are disheartened by the results and don’t submit them for publication. Or maybe you do submit them but they get rejected because your conclusion Coffee does not cause flu is uninteresting, has no impact, and it’s just so obvious. The failure of your experiment is never published and remains inaccessible to other researchers. Now consider the fact that, like you, there might be a hundred other researchers conducting the same experiment. It may happen that, in one of those experiments, the group that consumed coffee showed higher incidence of flu out of pure chance. When that lucky researcher submits his work for publication stating Coffee increases chances of catching flu, it gets published immediately because its a novel and sensational finding even though it is incorrect when you account for the past failures! If you happen to pickup the next issue of Health Today, you might get to read the article New research links coffee consumption to an increased risk of flu. The article will also quote an authoritative doctor offering a ridiculous explanation on how coffee decreases your immunity making you more susceptible to flu. Once the observations and the conclusions are established, it is easy to find an expert to conjure up a plausible causal link between the two.

Reboxetine was a drug manufactured by Pfizer and was prescribed for treatment of depression in Europe and UK in 2001. In 2010, after 9 years of usage, it was found to be ineffective for most patients (it was effective only for some special cases of depression). Publication bias during the trials had led to thousands of patients taking an ineffective drug. Universities and research institutes have started taking initiatives to encourage researchers to publish negative findings. Many organizations now make it mandatory to register a trial before commencing it and require the results to be reported irrespective of success. Let’s hope that these initiatives prove helpful.

We are fortunate to have easy access to information. It’s difficult to imagine the time when the only source of information we had were the handful of people around us. The printing press and the Internet has changed that, and we must take advantage of it. It’s not possible for us to verify everything we read. It would also be inadvisable to distrust all information. But we can choose when to be skeptical. We can afford to be relaxed and trusting when dealing with things that aren’t critical. But when it comes to things that matter such as our health, we must be careful!

If you liked the article, check out my other pieces on Medium, follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter, view my personal webpage, or email me at viraj@berkeley.edu.