The Great Purge of 1933

How Nazism Destroyed Science in Germany

This story is also available on Kindle!

“If the dismissal of Jewish scientists means the annihilation of contemporary German science, then we shall do without science for a few years!” — Adolf Hilter

Prior to World War II, Germany had led the world in science for more than one hundred and fifty years. Its reputation for excellence in chemistry, physics, biology, medicine and mathematics was rivaled, if at all, only by Britain(Medawar & Pyke, 2000). Of the 100 Nobel Prizes awarded between 1901 and 1932 (the year before Hitler came to power) 33 were awarded to Germans or scientists working in Germany. Britain had won 18, and the United States a mere six.

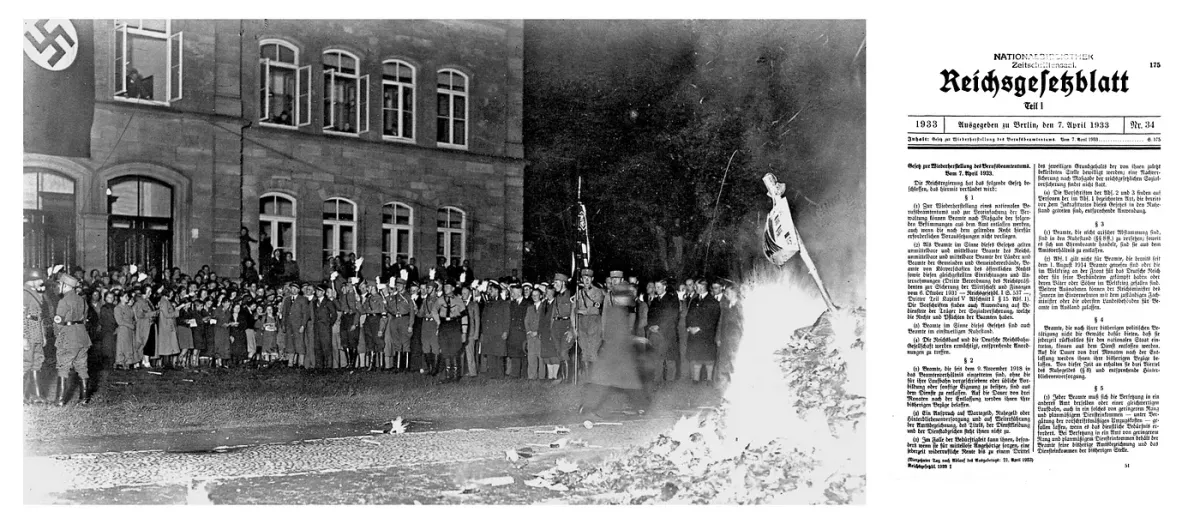

Then, as the result of a series of events following Hitler’s takeover of Germany in 1933 and the passing of the Berufsbeamtengesetz (“Law for the Restoration of the Professsional Civil Service”), in order to “re-establish a national and professional civil service”, members of certain groups of public employees began being dismissed from German universities. That is, civil servants who were not considered to be of “sufficiently Aryan” descent had to leave their jobs.

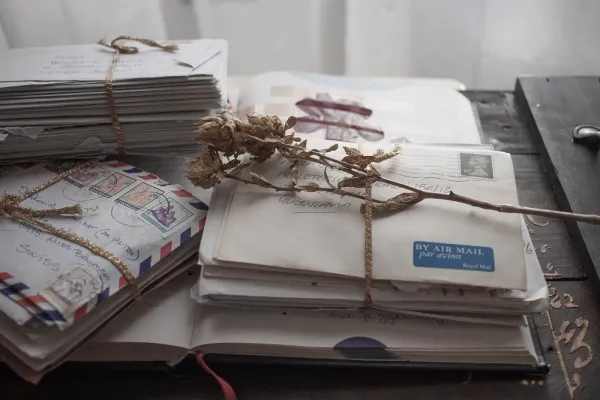

Shortly after the passing of the law, scientists and academics began being let go from their positions at the University of Göttingen, Humboldt University of Berlin and other prominent, world-class German universities (Heims, 1980 p. 165). Bücherverbrennung (book-burnings), märsche (marches) and propagandaagainst ideas, individuals and works considered Jewish, liberal or left-leaning began being commonplace. In a series of letters to his colleague in America Oswald Veblen, John von Neumann in the spring of 1933 wrote (Rédei, 2005):

“The news from Germany are bad: heaven knows what the summer term 1933 will look like.”

The term, and the coming years, looked like what has later been called a “great purge”, the mass emigration of world class scientists, academics and other intellectuals unlike any the world has ever seen before or since.

The outcome would be the downfall of what has been called the “the mathematical center of the universe” in Göttingen and the rise of the United States as the world’s foremost center of scientific research.

Background

On January 30th 1933, the President of Germany Paul von Hindenburgreluctantly appointed Nazi leader Adolf Hitler to be the Chancellor of Germany. After only two months in office, following the burning of the Reichstag building, the German parliament passed the “Enabling Act” giving the chancellor full legislative power for a period of four years. Following the death of von Hindenburg in 1934, Hitler later used the act to merge the offices of Chancellor and President, creating the new office of “Führer and Reichskanzler”. On April 3rd, John von Neumann (1903–1957), then in Budapest) wrote the following in a letter to Oswald Veblen (1880–1960) in Princeton:

Excerpt, letter from von Neumann to Veblen (April 3rd 1933)

It seems, that this Summer will be a endless series of sensations - and not always of the agreeable kind. [...] Please excuse in me that I am asking such a lot of questions. But you know, how these things interest me, and how little newspapers a[re] worth, if you want to find out anything [...]The news from Germany are bad: heaven knows what the summer term 1933 will look like. The next programm-number of Hitler will probably be annihilation of the conservative-monarchistic-party [...] I did not hear anything about changes or expulsions in Berlin, but it seems that the "purification" of universities has only reached till now Frankfurt, Göttingen, Marburg, Jena, Halle, Kiel, Köningsberg- and the other 20 will certainly follow. [...] It is really a shame, that something like that could happen in the 20th century.

By the middle of April of the same year, the Main Office for Press and Propaganda of the German Student Union proclaimed a nationwide “action against the un-German spirit”. Not long after, public Nazi marches on and around University campuses had become commonplace. Bücherverbrennung, book-burning ceremonies were held in protest of literature found to be sympathetic with socio-democratic, left-leaning and/or Jewish values.

The exclusion of "left", democratic, and Jewish literature took precedence over everything else. The black-lists [...] ranged from Bebel, Bernstein, Preuss, and Rathenau through Einstein, Freud, Brecht, Brod, Döblin, Kaiser, the Mann brothers, Zweig, Plievier, Ossietzky, Remarque, Schnitzler, and Tucholsky, to Barlach, Bergengruen, Broch, Hoffmannsthal, Kästner, Kasack, Kesten, Kraus, Lasker-Schüler, Unruh, Werfel, Zuckmayer, and Hesse. The catalogue went back far enough to include literature from Heine and Marx to Kafka.- Excerpt, The German Dictatorship (1970) by Karl Dietrich Bracher

Jewish Scholars

More than 250 Jewish professors and employees were fired from the University of Berlin from 1933–34 and numerous doctorates were withdrawn. Some 20,000 books written by “degenerates” and opponents of the Nazi regime were taken from the library to be burned in the Babelplatz starting in May of 1933. Reportedly, nazi minister of propaganda Joseph Goebbels gave a speech for the occasion, proclaiming the death of “Jewish intellectualism” (Isaacson, 2007).

Albert Einstein (left in 1932)

You know, I think, that I have never had a particularly favorable opinion of the Germans (morally and politically speaking). But I must confess that the degree of their brutality and cowardice came as something of a surprise to me. — Albert Einstein, May 30th (1933)

Albert Einstein (1879–1955) who openly opposed the Nazi regime, happened to be visiting the United States when Hitler rose to power. A visiting Professor at the California Institute of Technology on and off starting in December 1930, Einstein and his wife Elsa last left Germany for good two years later, in December 1932, prior to Hitler’s ascension. Despite holding a chair as Professor of Physics at the University of Berlin, he feared for the safety of both himself and his family, as a German magazine printed a list of “enemies of the German regime” with an accompanying picture marked “not yet hanged” with a $5,000 bounty (Jerome & Taylor, 2006).

When they closed up their summer house in Caputh in 1932, Einstein reportedly turned to his wife Elsa and said “Dreh dich um. Du siehst’s nie wieder” (Pais, 1982).

“Turn around. You will never see it again”

Einstein would go on to spend a period of time in the UK, before settling for good at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey in 1933 as one of the IAS’ six founding faculty members, alongside J. W. Alexander, John von Neumann, Marston Morse, Oswald Veblen and Hermann Weyl.

Albeit from afar, Einstein would still play an instrumental role in the rescue operations that would take place from 1933 up until to the beginning of the war. Writing to Professor Max Born at Göttingen at the end of May, his mixed emotions of enthusiasm and desperation for the mission afoot are apparent:

Letter from Einstein to Born (30th of May, 1933)

Dear Born. Ehrenfest sent me your letter. I am glad that you have resigned your positions (you and Franck). Thank God there is no risk involved for either of you. But my heart aches at the thought of the young ones. Lindemann has gone to Göttingen and Berlin (for one week). Maybe you could write to him here about Teller. I heard that the establishment of a good Institute of Physics in Palestine (Jerusalem) is at present being considered.[...]Two years ago I tried to appeal to Rockefeller's conscience about the absurd method of allocating grants, unfortunately without success. Bohr has now gone to see him, in an attempt to persuade him to take some action on behalf of the exiled German scientists. It is to be hoped that he'll achieve something. Lindemann has considered London and Heitler for Oxford. He has set up an organization of his own for this purpose, taking in all the English universities. I am firmly convinced that all those who have made a name already will be taken care of. But the others, the young ones, will not have the chance to develop.[...]Yours, Einstein

The “Lindemann” Einstein mentions in the letter was Frederic Lindemann(1886–1957), the most influential scientific advisor to the then-”MP in opposition for Woodford” Winston Churchill. Despite his German name, Lindemann was English and a physicist by training, and so got along with both Churchill, Einstein and their colleagues in government and academia, respectively.

Looking to appeal to both his sense of humanity and military strategy, Einstein went to Churchill in the summer of 1933 asking for help in bringing Jewish scientists out of Germany. Of the meeting — which was held at Chartwell — characteristic of both men’s reputations for eccentricity, someone later wrote

“Churchill wore a large Stetson hat and Einstein a white linen suit that looked like he had slept in it”

Known for his decisiveness, Churchill responded immediately by sending his friend Lindemann to Germany on a rescue mission to seek out and recruit Jewish scientists and offer them placements in British universities (Gilbert, 2007).

Lindemann’s first visit was to physicist Max Born.

Max Born (left in 1933)

“I’ve been promoted to an ‘evil monster’ in Germany and all my money has been taken away from me.”

German physicist Max Born (1882–1970) was one of six Jewish professors who in the spring of 1933 had been suspended from their positions in Göttingen as a result of the enactment of the Berufsbeamtengesetz. A future Nobel Prize winner in Physics, at the time he was among the world’s 3–4 foremost authorities on quantum physics, having supervised the likes of Pascual Jordan, Oppenheimer, Fermi as well as collaborated with Heisenberg, Pauli and Bohr. In his 1971 book The Born-Einstein Letters*, Born recounted his own version of the events that had ensued:

One day (at the end of April 1933) I found my name in the paper amongst a list of those who were considered unsuitable to be civil servants, according to the new "laws". After I had been given 'leave of absence', we decided to leave Germany at once. We had rented an apartment for the summer vacation in Wolkenstein in the Grödner valley, from a farmer by the name of Peratoner. He was willing to take us in immediately. Thus, we left for the South Tyrol at the beginning of May (1993); we took our twelve-year old son, Gustav, with us, but left our adolescent daughters behind at their German schools."- Excerpt, The Born-Einstein Letters by Max Born (1971)

On his way to Tyrol, on May 10th Born witnessed the book burnings first-hand and despite his typical quiet and calm demeanor reacted so furiously that his wife Heidi had to restrain him from intervening (Medawar & Pyke, 2000). Shortly after arriving at their destination, Lindemann visited, attempting to entice Born to accept a position at his alma matter Oxford. However, having spent time in Cambridge in the 20s, Born instead chose to accept a position as a “research student” at St. John’s College, Cambridge. Later, in 1936, he accepted a position as the Tait professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh, where he remained until 1952 before retiring to Göttingen.

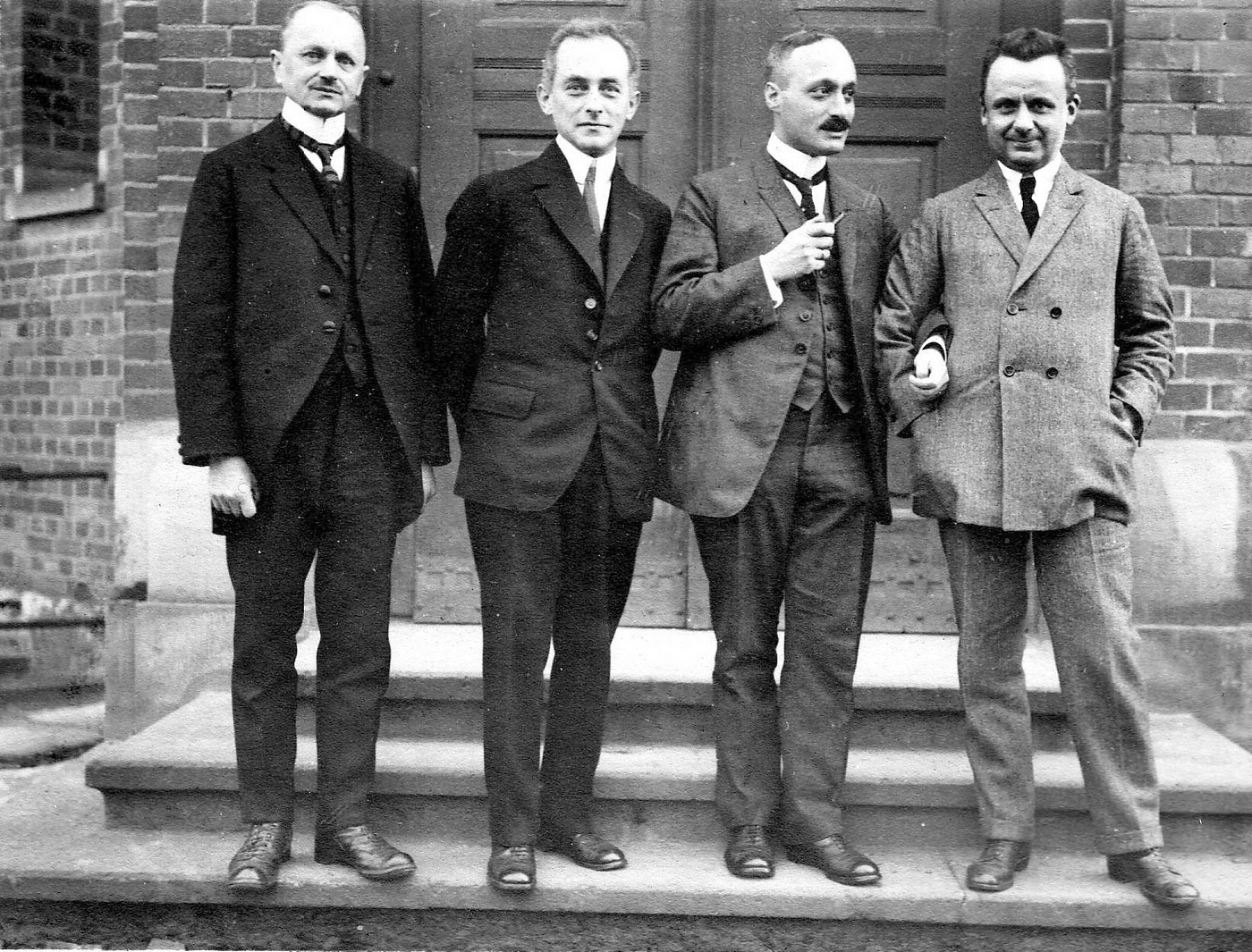

Heitler and London (both left in 1933)

As Einstein’s letter to Born recounts, Lindemann also considered recruiting Born’s former students Walter Heitler (1904–1981) and Fritz London (1900–1954). Heitler was a German physicist who made contributions to quantum electrodynamics and quantum field theory and had worked for a time as assistant to Erwin Schrödinger. Following his Habilitation in 1929 under Born, he remained at the University of Göttingen as a Privatdozent until 1933, when he was let go. Safely in the UK, Born later arranged for him to get a position as a research fellow at the University of Bristol, working under Nevill Francis Mott(1905–1996). Fritz London, also a physicist, similarly lost his position at the University of Berlin following the enactment of the Berufsbeamtengesetz. A collaborator of Heitler, London had helped redefine chemical bonds in the age of quantum theory. Following his dismissal, he took visiting positions in England and France before, like many others, emigrating to the United States before the war in 1939.

James Franck (left in 1933)

The other professor Einstein mentions, James Franck (1882–1964), was a German physicist and the 1925 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics (joint with his frequent collaborator Gustav Hertz) for “their discovery of the laws governing the impact of an electron upon an atom”. At the time of the purge in the spring of 1933, Franck was the head experimental physicist at the University of Göttingen, a position he had held for over thirteen years. A full professor, he was also the Director of the Second Institute for Experimental Physics in Göttingen. Alongside Born, Franck had built Göttingen’s physics department into one of the world’s finest (Rice & Jortner, 2010).

Although exempt from the Berufsbeamtengesetz law as a veteran of the First World War, as Einstein recounts to Born, Franck nonetheless submitted his resignation at Göttingen, the first academic known to have resigned in protest of the new laws. After a brief visit to the United States, he later took up a position at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, before returning to the U.S. in 1938, accepting a job offer at the University of Chicago.

Hans Bethe (left in 1933)

Physicist Hans Bethe (1906–2005) was similarly dismissed from his job at the University of Tübingen in Germany and so left for England after receiving and offer for the position of lecturer at the University of Manchester through his doctoral advisor Arnold Sommerfeld (1868–1951) and his associate William Lawrence Bragg (1890–1971) there (Bernstein, 1980).

Bethe eventually joined the faculty of Cornell University in 1935 and contributed to the Manhattan project as Head of the Theoretical division at Los Alamos. A nuclear physicist, through the course of his career he also made important contributions to astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics and solid state physics, winning the Nobel Prize in physics in 1967 for his work on the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis (Lee & Brown, 2007).

“The Martians of Budapest”

Einstein’s letter to Born also mentions the then-aspiring young Hungarian Edward Teller, one of four prominent “Martians of Budapest” who, due to their Jewish origin and Hungarian universities’ openly antisemitic policies at the time, were compelled to leave Europe for America in the 1930s. Interestingly and consequentially, all four contributed significantly to the development of the first atomic bomb, alongside Franck, Bethe and others:

- Edward Teller (1907–2003), a student of Born who would later be known colloquially as the “Father of the hydrogen bomb” had been in Copenhagen studying with Niels Bohr until just before Hitler fame to power. He was in Göttingen in the spring of 1933. From there he immediately left for England with the help of the International Rescue Committee, a global humanitarian aid founded in 1933 at the encouragement of Einstein. In England, Teller was welcomed at the University College of London, before being offered a full professorship at George Washington University in D.C., which he accepted in 1935.

- Eugene Wigner (1902–1995), the later Nobel laureate in Physics and fellow Manhattan Project member of Teller, had at the time of the purge been at Princeton University since 1930. Before that, he too had been at the University of Göttingen working both as an assistant to David Hilbert and alongside Hermann Weyl (1885–1955) on group theory as it applies to quantum physics. Reportedly, when he was first recruited for a one-year lectureship at Princeton, his salary increased seven-fold from what it had been in Europe (Szanton, 1992). However, following the expiration of his term in 1936, Princeton chose not to renew his position and so Wigner had to move to the University of Wisconsin. There he stayed for two years before returning to Princeton in 1938 to commence work on the Manhattan Project.

- Leo Szilard (1898–1964) who is now perhaps best known as the discoverer of the nuclear chain reaction, similarly as Teller left Germany for England in 1933. Reportedly, he transferred his savings of £1,595 (about £100,000) from Zurich to London and was able to live in hotels without work for over a year. His first job in England the next year came when he took up work as a physicist in St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, working on radioactive isotopes for medical purposes. He next travelled around the U.S. as a visiting researcher in 1938–1939, eventually settling at Columbia University. There, in collaboration with Walter Zinn, he took on the task of experimentally verifying the news brought to America by Niels Bohr in January 1939 that Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in Germany were claiming to observed barium in the residue after bombarding uranium with neutrons, demonstrating the previously unknown phenomenon of nuclear fission. Szilard and Zinn’s initial test that the fission of uranium produced more neutrons than it consumed helped Szilard later convince Enrico Fermi and Herbert L. Anderson (1917–1994) to conduct large-scale fission experiments on uranium to verify the possibility of a sustainable nuclear chain reaction.

Enrico Fermi (left in 1938)

Although himself Italian and Roman Catholic by origin, physicist Enrico Fermi (1901–1954) was like his German colleagues forced to escape Mussolini’s fascist Italy in 1938 because his wife Laura was Jewish.

The creator of the world’s first nuclear reactor, Fermi won the 1938 Nobel Prize in physics for his work on induced radioactivity. Before the war, like most word-class physicists he had spent a semester studying under Max Born at the University of Göttingen. There, in the middle of the 1920s he first met some of who would become the later protagonists of the nuclear age, including the “father of quantum mechanics” Werner Heisenberg and his collaborator Wolfgang Pauli. After this and several other research visits, he eventually settled at the Sapienza University of Rome after obtaining a full professorship there in 1926. A Nobel laureate, upon his emigration to America in 1939, Fermi was offered positions at five different universities, eventually settling on an offer from Columbia , where he had given summer lectures in 1936. There, he conducted the first nuclear fission experiment in the United States and with the help and encouragement of Szilárd, the first large-scale fission experiment using 200 kilograms of uranium oxide.

Szilard’s work on the nuclear chain reaction — eventually verified by Fermi and Anderson — later in the same year lead to his decision to contact Einstein and write the infamous Einstein-Szilárd letter to the Belgian Ambassador to the United States (as Belgian Congo was the best source of uranium ore) andPresident Franklin D. Roosevelt, arguing that the United States should start a nuclear program. Szilárd came to write the letter after conferring with both Wigner and Teller, who agreed that if America did not at once pursue nuclear research, German physicists working under the Nazi regime might lead to the development of atomic weaponry which could hold catastrophic consequences for the Allied forces. On July 12th 1939, Szilard and Wigner together drove in Wigner’s car to Long Island where Einstein was staying and composed the letter, which was mailed on August 2nd. In the letter, the three European émigrés famously warned Roosevelt that:

The Einstein-Szilárd Letter (August 2nd, 1939)

In the course of the last four months it has been made probable — through the work of Joliot in France as well as Fermi and Szilárd in America — that it may become possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium, by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium-like elements would be generated. Now it appears almost certain that this could be achieved in the immediate future.This new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable — though much less certain — that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed. A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory. However, such bombs might very well prove to be too heavy for transportation by air.[...]I understand that Germany has actually stopped the sale of uranium from the Czechoslovakian mines which she has taken over. That she should have taken such early action might perhaps be understood on the ground that the son of the German Under-Secretary of State, von Weizsäcker, is attached to the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut in Berlin where some of the American work on uranium is now being repeated.Yours truly,Albert Einstein

John von Neumann (left in 1933)

The perhaps most well-known “martian” of them all, John von Neumann (1903–1957), although not involved in the founding of the Manhattan project later contributed to it by way of his work on the mathematical modeling of explosions and in particular, the conceptualization and design of explosive lenses needed to compress the plutonium core of the “Fat Man” weapon later dropped on Nagasaki.

von Neumann, alongside Wigner was first recruited from Europe by Veblen to Princeton University in 1930. Him and Wigner had by that point collaborated on five papers and before that, actually attended the same Lutheran high school in Budapest in the 1910s. According to Wigner, they were invited to Princeton together on a recommendation from the university that they find and invite:

"..not a single person but at least two, who already knew each other, who wouldn't suddenly feel put on an island where they had no intimate contact with anybody. Johnny's name was of course well known by that time the world over, so they decided to invite Johnny von Neumann. They looked: who wrote articles with John von Neumann? They found: Mr. Wigner. So they sent a telegram to me also."- Excerpt, John von Neumann by Norman Macrae (1992)

von Neumann’s considerable research output taken into account, despite being 30 years old, he was offered a lifetime professorship at the newly-founded Institute for Advanced Study alongside Albert Einstein in 1933. In a letter to Oswald Veblen, von Neumann writes of his impression of the situation in Germany in April of that year (Rédei, 2005):

"You have probably read, that Courant, Born, Bernstein have lost their chairs, and J. Frank gave it up voluntarily. From a letter from Courant I learned 6 weeks ago (which is a very long time-interval now in Germany) that Weyl had a nervous break-down in January, went to Berlin to a sanatorium, but that he will lecture in Summer."

von Neumann would later be instrumental in helping his and Einstein’s friend Kurt Gödel escape occupied Austria in 1939, following the Anschluss. Although not Jewish, Gödel’s association with the Vienna Circle and his doctoral advisor Hans Hahn (1879–1934) had made him a target. In a letter to the founder of the IAS Abraham Flexner (1866–1959), von Neumann in September 1939 wrote (Rédei, 2005):

"The claim may be made with perfect justification that Gödel is unreplaceable for our education program. Indeed Gödel is absolutely irreplaceable; he is the only mathematician alive about whom I would dare to make this statement [...] I am convinced that salvaging him from the wreck of Europe is one of the great single contributions anyone could make to science at this moment."

Gödel was indeed offered a position at the IAS, which he assumed after World War II in Europe began, in 1940.

Richard Courant (left in 1933)

Among other prominent Jewish scholar forced to emigrate was, as von Neumann writes in his letter to Veblen, mathematician Richard Courant (1888–1972), one of Göttingen’s three institute heads. He left Germany for Cambridge in 1933, as he had lost his position, due not to being Jewish (also being a veteran of the First World War), but due to his membership in the social-democratic political left (Schappacher, 1991). Student of Hilbert, Courant had obtained his doctorate in 1910. Upon Erich Hecke’s retirement at Göttingen in 1921, Courant was offered the position of full professor, and later founded the Mathematical Institute there, which he headed as director from 1928 until his expulsion in 1933.

Initially attempting to stay in close geographical proximity to Germany, Courant first accepted a position in Cambridge, but grew so homesick that he returned to Germany after a year, only to realize again that there was no way for him to stay permanently. He re-emigrated, this time to New York University where he would remain for the rest of his life, building up a large and flourishing mathematics department (Medawar & Pyke, 2000).

Other students of Hilbert at Göttingen, Felix Bernstein (1878–1956) and Edmund Landau (1877–1938) were also forced out, as was Hilbert’s student Hermann Weyl (1885–1955), three years after being appointed his successor. Initially having been offered von Neumann’s position at the Institute for Advanced Study, Weyl changed his mind as the political situation in Germany grew worse (Weyl was a Christian, but his wife Helene was Jewish), and joined the IAS in September of 1933.

Those Who Remained

Nobel Laureate in Physics and personal friend of Einstein, Max Planck (1858–1947) was 74 years old when the Nazis came to power. Although his friends and colleagues fled, himself, a Lutheran, tried to “persevere and continue working”, hoping the crisis would abate and the political situation would improve. Later founder and President of the Max Planck Society Otto Hahn (1879–1968), despite supposed Jewish ancestry (Riehl & Seitz, 1996), remained in Germany during the rise of the Nazis, discovering nuclear fission in 1938 and being awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1944. An opponent of national socialism, Einstein later wrote that

“Hahn was one of the very few who stood upright and did the best he could in these years of evil” — Albert Einstein

Indeed, the only known case of a German scientist refusing on moral grounds to succeed an expelled Jewish colleague was Otto Krayer (1899–1982), who in response to a job offering at the University of Düsseldorf wrote the following in protest of the purge of his colleagues (Medawar & Pyke, 2000):

I prefer to forgo this appointment, though it is suited to my inclination and capabilities, rather than having to betray my convictions, or that by remaining silent I would encourage an opinion about me that does not correspond with the facts. — Otto Krayer, Assistant Professor of Pharmacology in Berlin

In response, Krayer was immediately dismissed from his post at the University of Berlin for refusing to accept the appointment. Wolfgang Haubner later reported about a meeting with Krayer in his diary on July 4th 1935, stating

“On the way I spoke with Krayer who justified his refusal to return to Germany with the impossibility of taking the Hitler oath”.

Two years later, in 1937, Krayer was later appointed as an Associate Professor at Harvard University. He lead Harvard’s Department of Pharmacology from 1939 to 1966, being awarded numerous academic honors. The news of his actions in 1933 became public in an article written by the son of Krayer’s doctoral advisor Paul Trendelenburg (1884–1931), who closed his essay with the following words:

“Considering the horrors of the Third Reich, his deeds should be a comfort to us. When looking for a role model for the young generation, it is found in Otto Krayer. May the memory of this one righteous person never fade.” — Ullrich Trendelenburg

In 1934, David Hilbert (1862–1943) who had born witness to many of his students and colleagues having to flee, was dining with the Nazi minister of education Bernhard Rust. When Rust asked, “How is mathematics at Göttingen, now that it is free from the Jewish influence?” Hilbert famously replied,

“There is no mathematics in Göttingen anymore.”

Those interested in reading more about the purge of scientists from Nazi Germany, although flawed, are encouraged to obtain the book Hitler’s Gift* by Medawar and Pyke (2000).