P vs. NP — What Is The Difference Between Solving A Problem And Recognizing Its Solution?

Diving into the most notorious open question in Computer Science and its far-reaching philosophical consequences.

From the dawn of history, Humans have been a problem-solver species. From early agriculture to space exploration, solving mathematical problems seems to be a critical factor in human survival. Since the ’70s, some computational problems that once were tedious to solve have become solvable in a split of a second, mainly due to the exponential growth in processing power. However, some unique problems remain indifferent towards technological advancement, as even for the most powerful computers, solving them takes more time then a human lifetime, even if the problem is within a reasonable scale. In fact, modern encryption relies on the fact that it’s effectively impossible to factor the product of large primes. These problems seem to share a common difficulty that is at the heart of the P versus NP enigma — What is feasible, and what is effectively impossible?

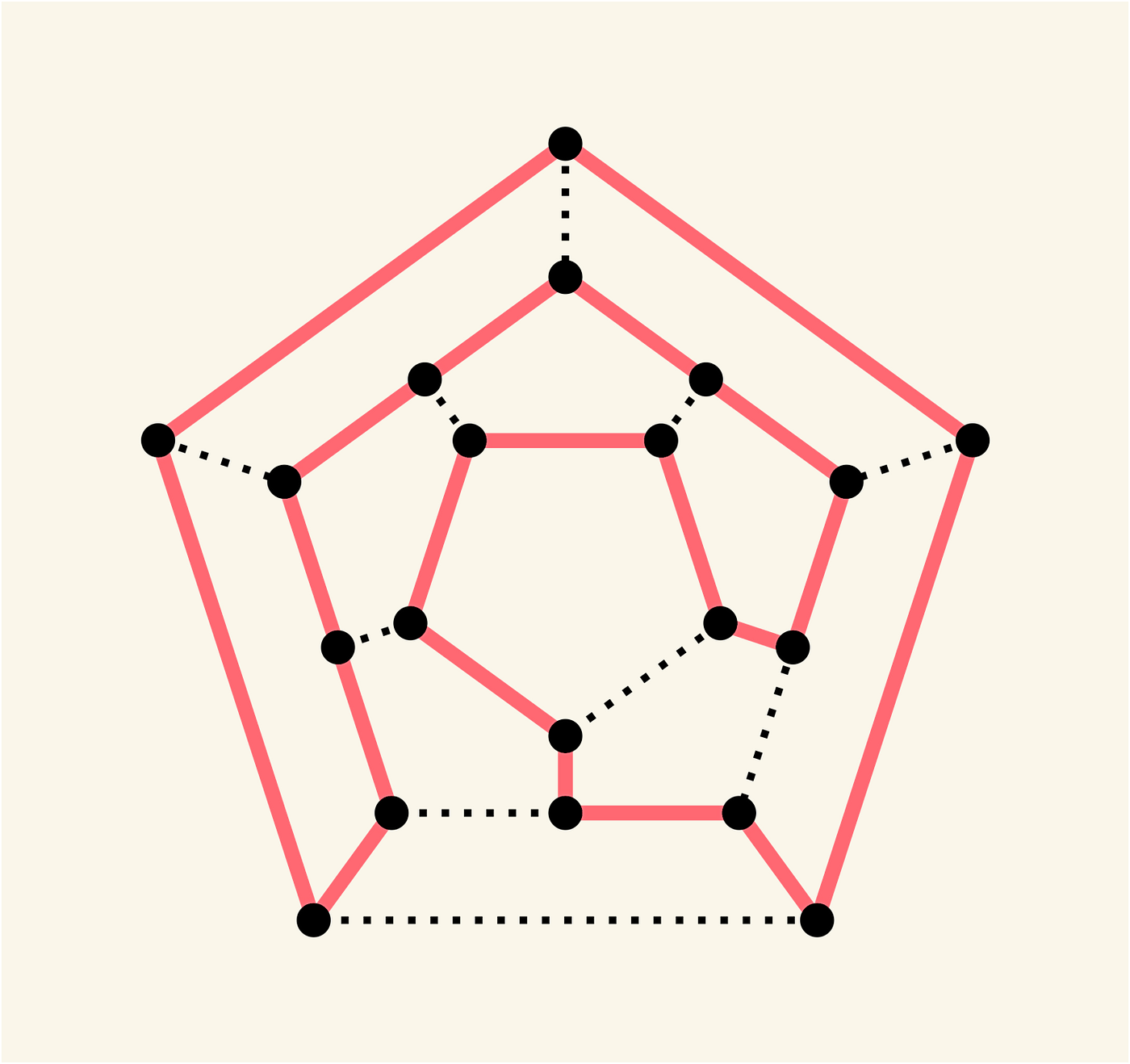

In1859, the Irish mathematician William Hamilton illustrated a mathematical game which is called Icosian. This game was played on a wooden dodecahedron surface, which consists of 20 corners (vertices). Each of these corners was labeled with the name of a city. The game’s objective was to find a cycle that visits every vertex exactly once and then returns to the starting point. This kind of path is called a Hamiltonian cycle. This simple game gave birth to a significant problem in Graph Theory named The Hamiltonian Cycle Decision Problem — Given an arbitrary graph, how can we know whether it contains a Hamiltonian cycle?

Given a Graph, determine whether it contains an Hamiltonian cycle.

One approach to solving this problem is by traversing any possible path in the graph and checking whether the path is a Hamiltonian cycle. However, since the number of possible paths can reach up to n!, even a graph with only 40 vertices might contain more then Quattuordecillion (10⁴⁵) paths, making the problem almost impossible to solve in a reasonable time, even for the most powerful processors. Furthermore, even if we somehow manage to build a super-processor that can handle this computation, due to the factorial dependency between the number of vertices to the number of paths, even the slightest addition of vertices to the graph would require a radical increase in processing power. We can say that the radical nature of the factorial growth makes this problem more difficult than other problems. This is the intuition behind the hardness of Mathematical problems — A problem is considered harder if the resources required to solve it grows radically when the input grows.

To formalize this idea, computer scientists use the scale of Time complexity. Time complexity refers to how many steps are needed to solve a problem and how the number of required steps scales up with the problem's size. Given an algorithm, the algorithm’s Time Complexity is described as an asymptotical function that is dependent on the algorithm’s input size. It is used to classify algorithms according to how their number of steps or space requirements grow as the input size grows.

“The asymptotic viewpoint is inherent to computational complexity theory, and reveals structure which would be obscured by finite, precise analysis.”

— Avi Wigderson

A fundamental distinction is made between algorithms that have a Polynomial Time Complexity, where their complexity function is a Polynom, to those that have a more radical complexity function. This distinction is made mainly because Polynomial growth is considered to be more moderate than others, in the sense that large changes in the input size would not cause a radical increment in required steps . A Polynom is a construct that involves only the operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and non-negative integer exponents, thus never introduces an Exponential or a Factorial growth. The choice of polynomial-time to represent efficient computation seems arbitrary; however, it has justified itself over time from many perspectives. For instance, the closure of polynomials under addition, multiplication, and composition preserve the notion of efficiency under natural programming practices, such as chaining programs into a sequence or nesting a program within another program.

Algorithms that have a Polynomial Time Complexity are referred to as “efficient”.

Over the years, there were many tryouts to solve the Hamiltonian Cycle Decision Problem efficiently. One of them is the Held-Karp algorithm, which manages to solve this problem in Exponential time. Still, no known algorithm can solve this problem in Polynomial-time, and therefore, it’s still considered a hard problem.

However, an interesting phenomenon occurs: Even though we can't efficiently solve this problem, given a path in the graph, we can at least efficiently check whether it is a Hamiltonian cycle — Since the maximal number of vertices in a simple cycle is n, then the time required to traverse a path is polynomially bounded to n.

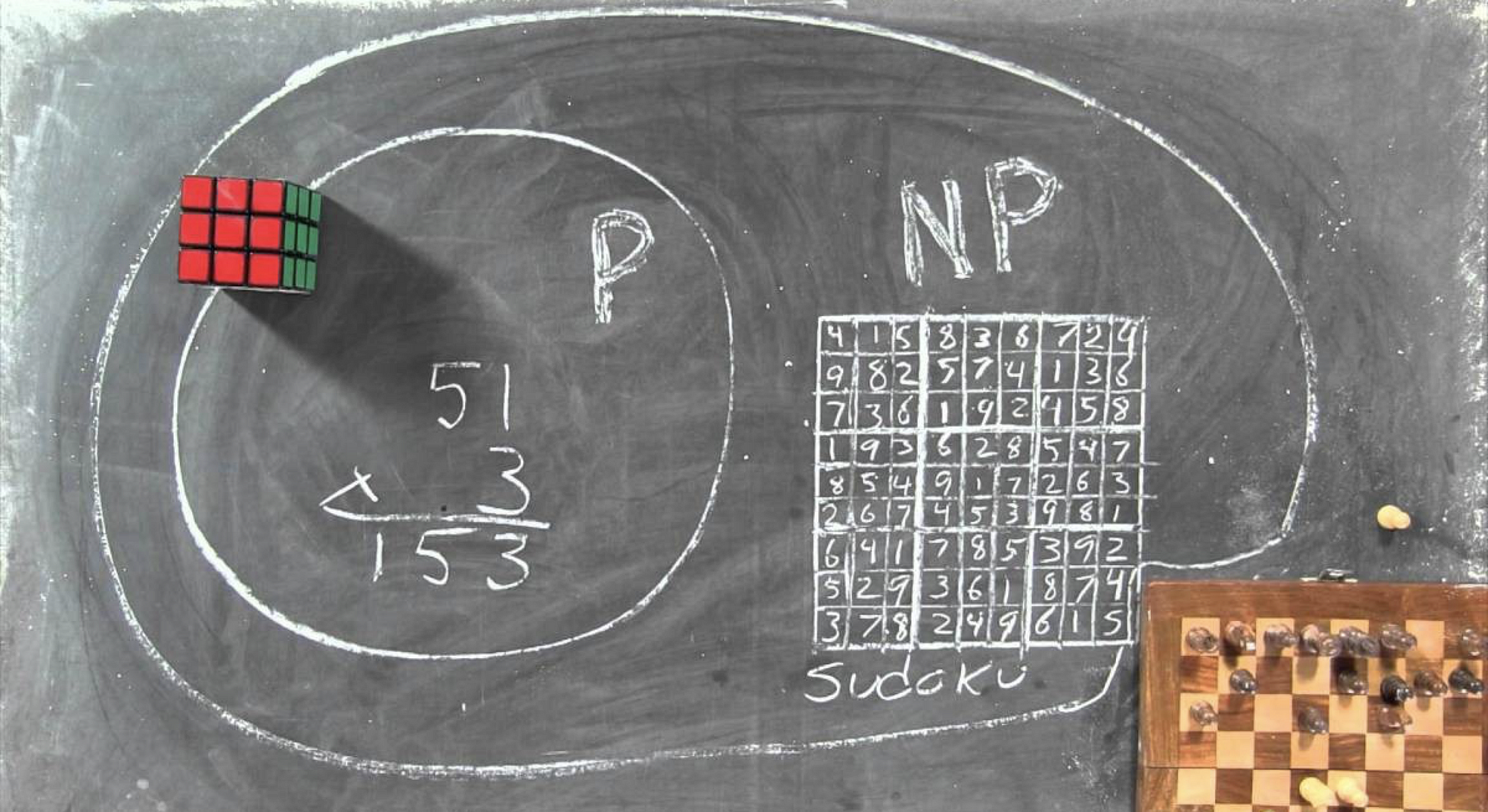

This phenomenon occurs in other difficult problems, such as the Sudoku Decision Problem — Given an incomplete Sudoku grid, we wish to know whether it has at least one valid solution. Any proposed Sudoku solution can be easily verified, and the time to check a solution grows polynomially as the grid gets bigger. However, all known algorithms for finding solutions take, for difficult examples, time that grows exponentially as the grid gets bigger. Similar to the Hamiltonian Path decision problem, there isn’t any known algorithm that can efficiently solve the Sudoku decision problem, but, given a solution, the solution could be efficiently verified. It appears that many other decision problems share this property — Regardless of whether they can be solved efficiently, their proposed solutions can be efficiently verified. This set of problems is defined as NP.

A Decision Problem is in NP if its solutions can be efficiently verified.

The acronym NP stands for nondeterministic polynomial time (despite the common belief that NP means “Not P”).

Thinking further about the relationship between the solvability of a problem and its solutions' verifiability brings us to the next point: If a decision problem is efficiently solvable, then its solutions must be efficiently verifiable. Why? Because if a decision problem is efficiently solvable, it means that we can find its solutions efficiently. Then, given a proposed solution, we can verify it simply by comparing it with the problem’s actual solutions. Put differently, the correctness of the algorithm generating the solution automatically certifies that solution. From this conclusion, it is evident that NP — the set of all decision problems in which their solutions are efficiently verifiable, contains a subset of problems that are also efficiently solvable. This subset is defined as P.

P is the set of all decision problems that are efficiently solvable. P is a subset of NP.

The Hamiltonian Path Decision Problem has an efficient algorithm that can verify its solutions; hence, it is in NP. One may wonder whether this problem is in P. Well, on the one hand, there is no knowledge about an efficient algorithm that solves this problem. On the other hand, there is no proof that such an algorithm doesn’t exist. In fact, there is still a chance that such an algorithm does exist and hasn’t been discovered yet. The same goes for the Sudoku Decision Problem, and, in fact, for many other major problems, including the Boolean satisfiability problem, the Travelling salesman problem, the Subset sum problem, the Clique problem, the Graph coloring problem, and others — Even though we have proved that those problems are in NP, there is no proof of the fact that they are outside of P. This is exactly what the P=NP question is all about:

Do P and NP are actually the same? If Yes, it means that all the problems in NP can be efficiently solved even though we still haven’t found the mysterious algorithms that achieve that. Otherwise, there are problems in NP that are impossible to solve efficiently, and any attempt to do so would mean a complete waste of our time and efforts.

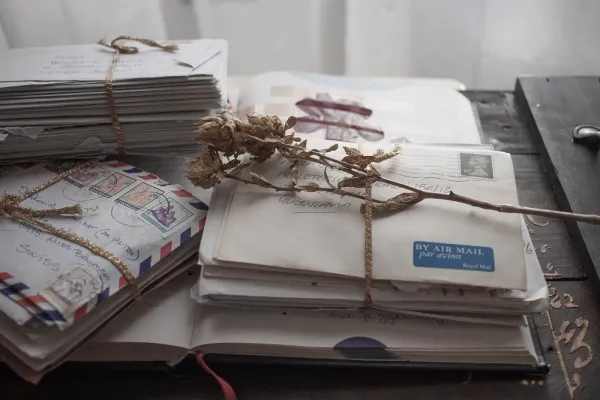

Most of the time, not being able to solve problems efficiently is a negative thing. However, in some cases, we could gain from a problem’s “hardness”. The main attribute of problems that are in NP and not in P is that it is hard to solve them, but easy to verify their solutions. This kind of asymmetryis especially useful in the field of Cryptography — Information can be “locked behind” a hard problem. Any brute-force attack would fail to unlock the information in a reasonable time, whereas any previous knowledge about the solution (a “key”) could be verified efficiently and therefore permit access. The most prominent example of this concept is the RSA public-key Cryptosystem, which is based on the Prime Factorization Problem.

Given two positive integers n and k, decide whether n has a prime factor smaller than k.

— The Prime Factorization Decision Problem

This problem is known to be in NP since its solutions can be efficiently verified: Given an integer c, it takes a Polynomial-time to know whether c is a prime smaller than k and is a factor of n. However, no known algorithm can solve this problem in Polynomial-time. Therefore, using two considerably large prime numbers, it is possible to compute their multiplication, which is used to generate a public key and a private key. The public key can be known by everyone, and it is used for encrypting messages. Messages encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted in a reasonable amount of time using the private key, assuming that there is no efficient way to factorize a large integer into its prime factors.

However, if P=NP, then the last assumption is false. Why? If P equals NP, then the Prime Factorization Problem is in P, meaning that it can be solved efficiently. Hence, once such an algorithm is found, any public key could be decrypted in a reasonable amount of time without the need for a private key, making the entire RSA Cryptosystem completely vulnerable, at least in the theoretical sense.

But the negative sides of P being equal to NP are relativity insignificant compared to the potential benefits it holds. There are literally thousands of NP problems in Mathematics, Optimization, Artificial Intelligence, Biology, Physics, Economics, and Industry, which arise naturally out of different necessities, and whose efficient solutions will benefit us in numerous ways. Proving that P=NP would mean that all those difficult problems can be solved in a Polynomial-time, which would lead to a massive intellectual pursuit after those remarkable algorithms. Once revealed, those algorithms would potentially boost human progress far beyond our grasp.

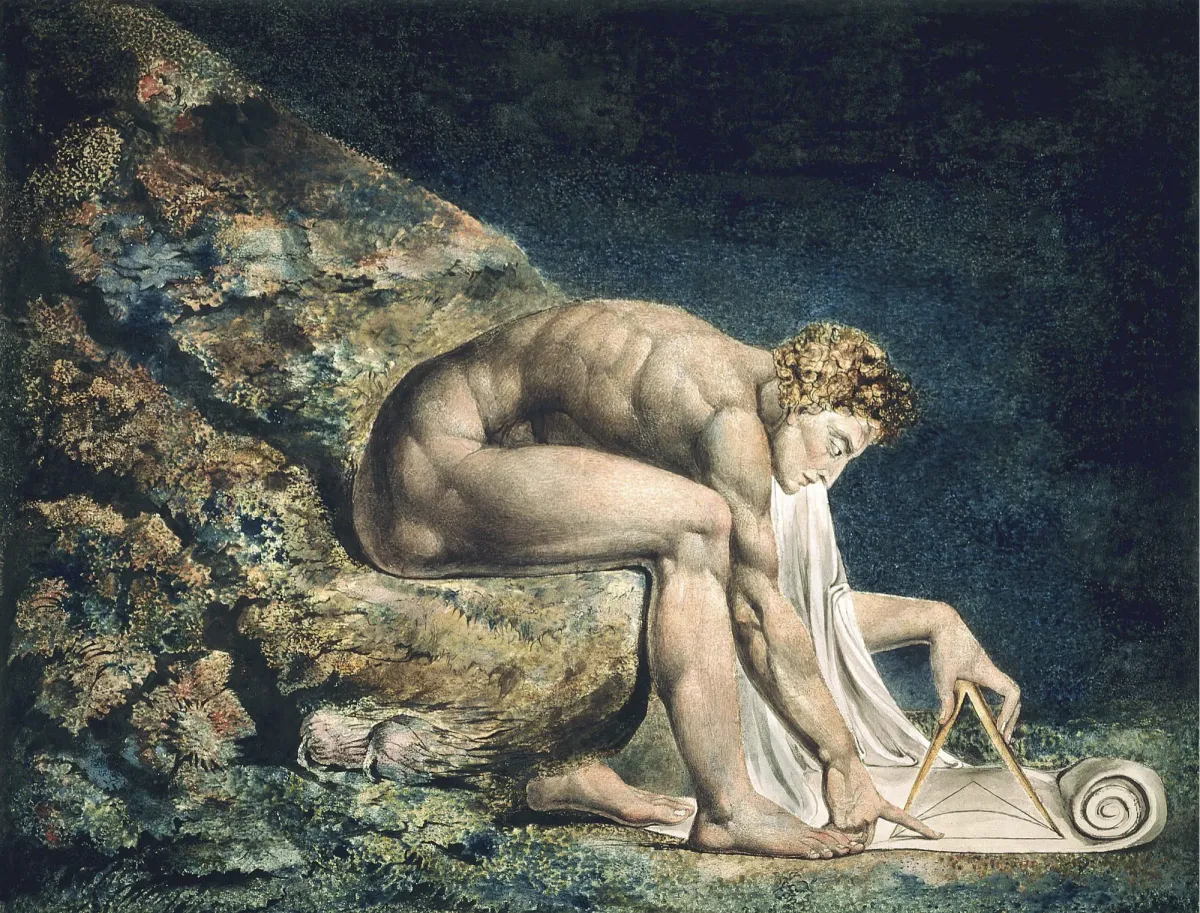

Even such consequences may pale into insignificance compared to the revolution an efficient method for solving NP problems would cause in mathematics itself.

Consider the well-known Pythagorean theorem as an example, which states the relation a²+b²=c² between the legs and the hypotenuse of a right triangle. This theorem has 370 known proofs. Each of those proofs is a possible solution for the following decision problem: “Is the Pythagorean theorem correct?”. This idea can be generalized:

If T is a theorem and p is its proof, then p is a solution for the decision problem: “Is T correct?”

This relation between mathematical theorems to decision problems allows us to generalize the discussion regarding P versus NP — If a proof’s correctness can be verified in Polynomial-time, then the corresponding decision problem is in NP (Since the proof is a proposed solution for that decision problem). In a world where P equals NP, such a decision problem is in P, meaning that it can be solved in Polynomial-time. Solving such a decision problem is essentially finding proof for theorem T. This could imply, to some extent, that proving a mathematical theorem is not significantly harder then inspecting the correctness of a given proof.

P equals NP may imply that proving a mathematical theorem is not fundamentally harder than verifying the correctness of its proof.

The last conclusion is truly remarkable considering that every mathematical proof can be formalized into a series of well-defined logical statements, which could be processed by a computer program to verify that proof automatically. Hence, P equals NP would mean that proving mathematical theorems can be done by a simple computer program.

“P equals NP would transform mathematics by allowing a computer to find a formal proof of any theorem which has a proof of a reasonable length, since formal proofs can easily be recognized in polynomial time.”

— Stephen Cook

One psychological reason people feel that P=NP is unlikely is that tasks as prooving mathematical theorems often require a degree of creativity, which we do not expect a simple computer program to have.

“We admire Wiles’ proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem, the scientific theories of Newton, Einstein, Darwin, Watson and Crick, the design of the Golden Gate bridge and the Pyramids, and sometimes even Hercule Poirot’s and Miss Marple’s analysis of a murder, precisely because they seem to require a leap which cannot be made by everyone, let alone by a simple mechanical device”

— Avi Wigderson

The above point leads us to a discussion about the very nature of the human brain. While science is extremely far from understanding the brain’s mechanism, the laws of physics govern its behavior. As such, and like every other natural process, the brain is an efficient computational device. Hence, any solution to any problem that has been recognized by the brain, has been, by definition, recognized efficiently. Therefore, P equals NP may imply that the brain is capable of solving those problems with the same efficiency.

“If P = NP, any human or computer would have the sort of reasoning power traditionally ascribed to deities, and this seems hard to accept.”

— Avi Wigderson

The idea by which amazing discoveries such as Wiles’s proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem or Einstein’s relativity could be produced by a mindless robot is not intuitive for most people, as they share a strong opinion by which creativity has been absolutely essential for reaching such insights.

“If P=NP, then the world would be a profoundly different place than we usually assume it to be. Everyone who could appreciate a symphony would be Mozart.”

— Scott Aaronson

Complexity theorists generally believe that P doesn't equal NP, and such a beautiful world cannot exist. In 2000, the Clay Math Institute named the Pversus NP problem as one of the seven most important open questions in mathematics and had offered a million-dollar prize for a proof that determines whether or not P = NP. ■

🎗 For more, visit my blog.