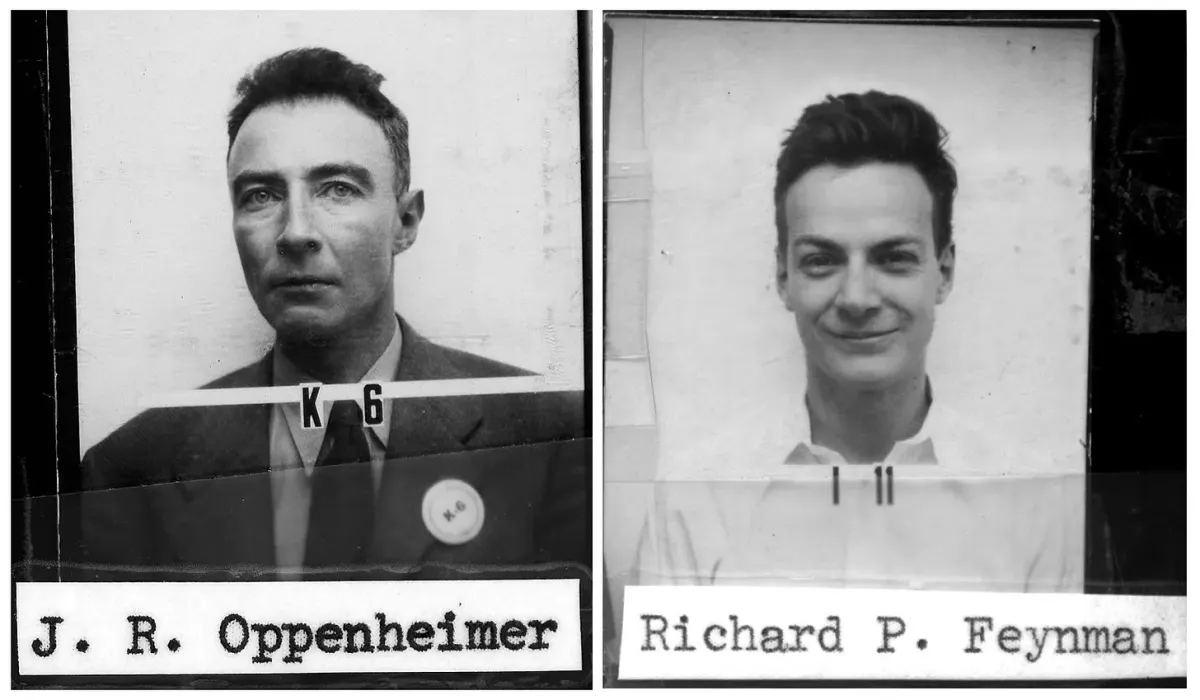

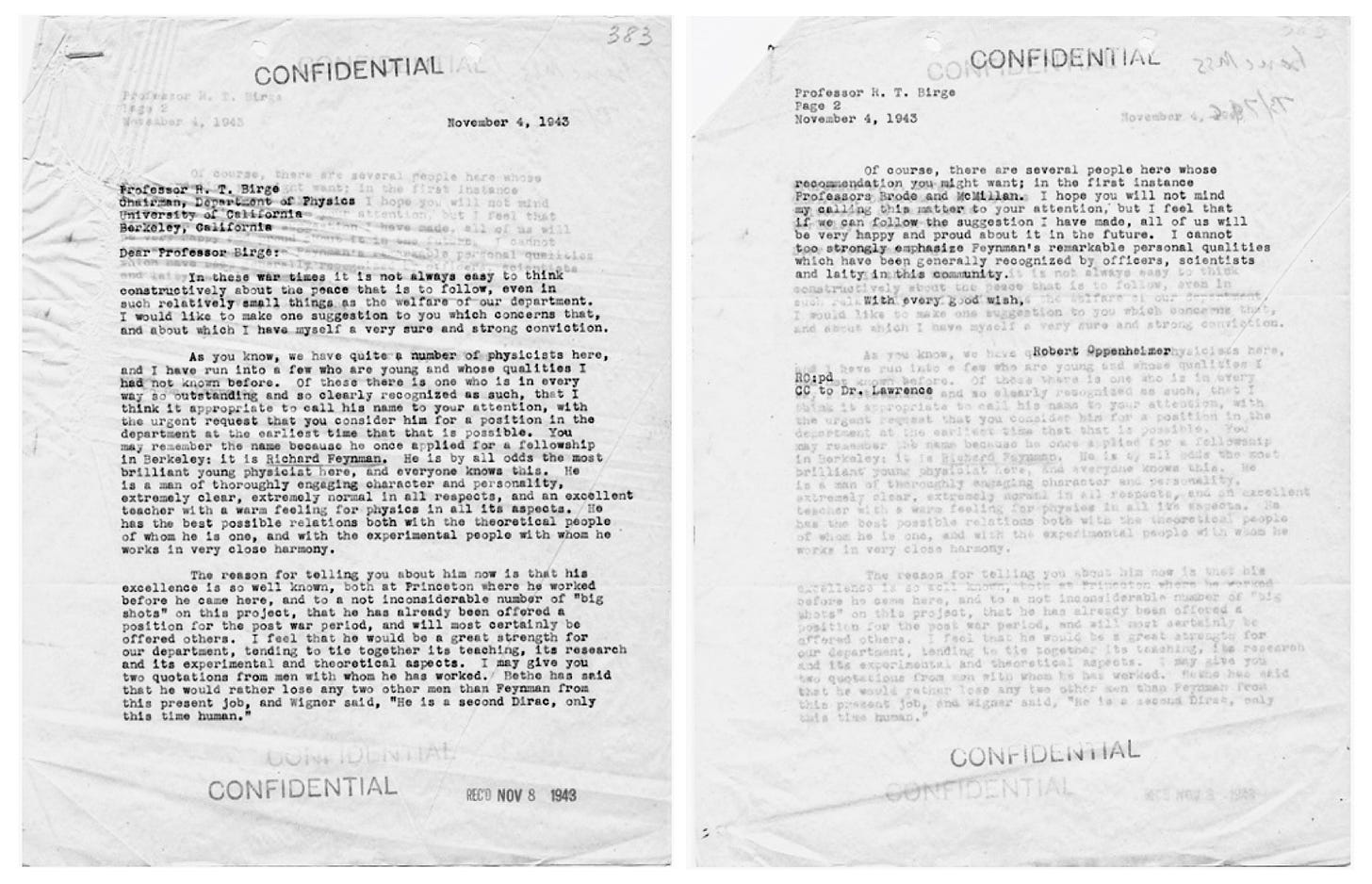

Oppenheimer’s Letter of Recommendation for Richard Feynman (1943)

Let’s journey back to November 1943. The Manhattan project is in its fourth year of operations, and J. Robert Oppenheimer’s Los Alamos Laboratory is eleven months into its mission of designing and building the first atomic bomb.

“He is a second Dirac, only this time human”

Let’s journey back to November 1943. The Manhattan project is in its fourth year of operations, and J. Robert Oppenheimer’s Los Alamos Laboratory is eleven months into its mission of designing and building the first atomic bomb. Oppenheimer had in 1942 been headhunted to the project by its Director, Lieutenant General Leslie Groves (1896–1970) on the strength of the recommendation of physicist Arthur Compton (1892–1962). He was 39 years old at the time, and came to the project already a Professor of Physics at the University of California, Berkeley. There, starting in the mid 1930s he had worked on deuteron-induced nuclear reactions, the so-called Oppenheimer-Phillips process, whose experiments were conducted at the newly built UC Berkeley cyclotron.

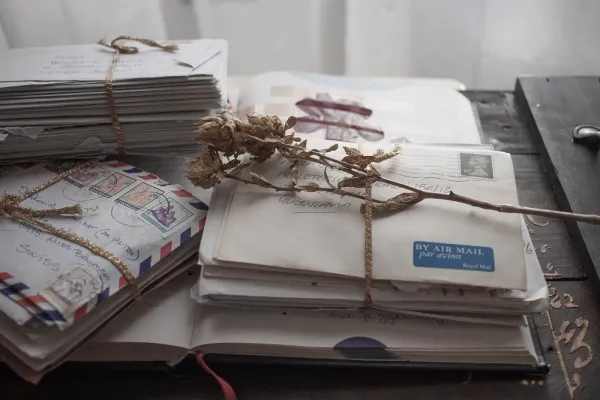

Although a classified endeavor, it was not uncommon for scientists and engineers on the project to communicate between themselves in letter-form about how things were proceeding. Indeed, communication across both institutions and scientific branches was imperative for ensuring a successful “Project Y”. Classified, of course, many such letters have since been made available to the public. When reading through Oppenheimer’s communications, one in particular stands out.

In the midst of what would six months later evolve into a crisis of sorts over the design of the atomic weapon, Oppenheimer in November of 1943 took the time to write Raymond T. Birge (1887–1980), the Head of the Department of Physics at UC Berkeley. The purpose of the letter was singular and simple: Oppenheimer was asking his peace-time boss to send an offer of employment to a promising young physicist working for him, Dr. Richard P. Feynman (1918–1988).

The Letter

“In these war times it is not always easy to think constructively about the peace that is to follow”

Oppenheimer’s letter starts out as one might expect in the midst of a war, acknowledging the current situation and making clear that his motivation for the letter is not related to the war-effort:

Dear Professor Birge.

In these war times it is not always easy to think constructively about the peace that is to follow, even in such relatively small things as the welfare of our department. I would like to make one suggestion to you which concerns that, and about which I have myself a very sure and strong conviction.

Positively gloating about the 25-year-old Feynman, Oppenheimer makes no qualms about his intention in writing the letter:

As you know, we have quite a number of physicists here, and I have run into a few who are young and whose qualities I had not known before. Of these there is one who is in every way so outstanding and so clearly recognized as such, that I think it appropriate to call his name to your attention, with the urgent request that you consider him for a position in the department at the earliest time that that is possible.

Feynman had previously applied for a fellowship at UCB. Now, Oppenheimer was appealing to the very Head of the Department on his behalf (by all accounts unbeknownst to Feynman) to offer him a permanent position on the strengths of the impressions he had made since arriving in the beginning of April:

You may remember the name because he once applied for a fellowship in Berkeley: it is Richard Feynman. He is by all odds the most brilliant young physicist here, and everyone knows this. He is a man of thoroughly engaging character and personality, extremely clear, extremely normal in all respects, and an excellent teacher with a warm feeling for physics in all its aspects. He has the best possible relations both with the theoretical people of whom he is one, and with the experimental people with whom he works in very close harmony.

Oppenheimer opines on, positively gloating about the young Feynman:

The reason for telling you about him now is that his excellence is so well known, both at Princeton where he worked before he came here, and to a not inconsiderable number of "big shots" on this project, that he has already been offered a position for the post war period, and will most certainly be offered others. I feel that he would be a great strength for our department, tending to tie together its teaching, its research and its experimental and theoretical aspects.

To put a fine point on it, Oppenheimer drives his argument home by citing two such “big shots”, Feynman’s supervisor of the theoretical division Hans Bethe (1906–2005) and Eugene Wigner (1902–1995), both later Nobel laureates:

I may give you two quotations from men with whom he has worked. Bethe has said that he would rather lose any two other men than Feyman from this present job, and Wigner said, "He is a second Dirac, only this time human."

Paul Dirac (1902–1984), of course, was renowned for his eccentric personality. Feynman’s hero, the two later met on at least three occasions.

Of course, there are several people here whose recommendation you might want; in the first instance Professors Brode and McMillan. I hope you will not mind my calling this matter to your attention, but I feel that if we can follow the suggestion I have made, all of us will be very happy and proud about it in the future. I cannot too strongly emphasize Feynman's remarkable personal qualities which have been generally recognized by officers, scientists and laity in this community.

With every good wish,

Robert Oppenheimer