Gödel’s Constitutional Quarrel

“The examiner was intelligent enough to quickly quieten Gödel and say ‘Oh god, let’s not go into this’ and broke off the examination at this point, greatly to our relief” — Oskar Morgenstern

Kurt Gödel (1906–1978) was the greatest logician who ever lived. At the age of 24, he revolutionized our understanding of the limits of epistemology — the theory of knowledge—by proving mathematically that all formal systems of logic are inherently incomplete. In a highly technical paper of 26 pages, Gödel showed how, no matter how comprehensive a system of rules, laws or axioms we devise, there will always be true and false statements which ‘fall through the cracks’, meaning they cannot be shown rigorously to belong to either classification. The consequences of his discovery spanned not only the foundations of mathematics, logic and philosophy, but indeed also spurred the development of the then-nascent fields of computer science, information theory and artificial intelligence.

Gödel’s Brilliant Madness

A meticulous man, perhaps the most meticulous man, Gödel arrived at his proof in the same way he arrived at most of his beliefs, by a combination of deep skepticism, rigor and, some say, pathological pessimism. Gödel would indeed spend the whole of his life in a battle against his two fiercest enemies: a morbid obsession with illness and death and, as a result, poor physical health. A lifelong iophobe, Gödel feared nothing more than being poisoned, and so made sure to only eat foods prepared for him and tasted by his wife Adele. Having grown up in apartments in Vienna heated by coal and coke, he obsessed over what he called “bad air” and “gases”, packing up and moving several times and refusing for most of his life to sleep in places warmed by central heating.

Gödel had fled the Nazi regime in Austria in 1940 following Hitler’s Anschluss of his native country. A visiting professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, he spent the war years contemplating what he had experienced in Europe in an eternal — often times losing — battle against his own mind and its appetite for paranoid, cynical interpretations of reality.

Becoming an American Citizen

When the time came for Gödel to become an American citizen, he invited his friends Oskar Morgenstern and Albert Einstein to come along as witnesses to his citizenship hearing. A “very thorough man” according to his close friend Morgenstern, Dr. Gödel spent the months leading up to this hearing “informing himself about the history of North America by human beings”. For Gödel, such an inquiry would never have been complete without a sufficiently thorough study of all matters of American history, including the history of Native Americans, their tribes, the early settlers, the Civil War, Princeton, New Jersey, where “the borderline was between borough and the township”, “how the Borough Council was elected, the Township Council, who the Mayor was, how the Township Council functioned” and so on.

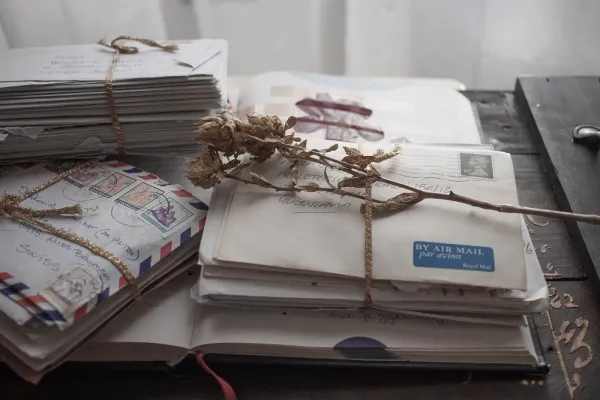

“I tried, to explain that all of this was totally unnecessary, of course, but with no avail”,Morgenstern later recalled in a memorandum. Gradually, as the months wore on, Gödel “proceeded to study American history, concentrating in particular on matters of constitutional law”. Morgenstern (who himself was an immigrant and took the same examination in 1944) “tried to convince him that such questions never were asked, that most questions were truly formal and that he would easily answer them; that at most they might ask what sort of government we have in this country or what the highest court is called”. Gödel nonetheless persisted, immersing himself deeper and deeper in his study of the American Constitution.

A scientist held in the highest possible esteem by colleagues, Gödel was in the 1930s and 40s part of a close-knit community of scholars in Princeton, the likes of which the world has likely never seen before or since. The most famous scientist in the world, Albert Einstein, had arrived in 1933. He was closely followed by a group of Hungarian geniuses lead by John von Neumann (1903–1957), sometimes referred to simply as ‘the smartest person who has ever lived’. The assembly of European emigres in Princeton in the 1930s and 40s was indeed so dense that the resultant mixture of accents spoken around Princeton University would be colloquially known as Fine Hall English, for the building the department of mathematics was housed in at the time. All of them looked up to Gödel, perhaps even more so than to anyone else. Before his death, Albert Einstein (1879–1955) himself told Morgenstern that even though “my own work no longer meant much, that he came to the Institute merely … to have the privilege of walking home with Gödel”. von Neumann, who had been in the audience when Gödel presented his breakthrough 1931 paper, called him “absolutely irreplaceable”, “in a class by himself”, asking later — upon von Neumann’s nomination to full professor — “How any of us can be called professor when Gödel is not?”

The Hearing

Still several months ahead of his citizenship examination in 1947, Gödel was conferring with his friend Morgenstern with increasing frequency, when “then came an interesting development”. As Morgenstern later recalled, “He rather excitedly told me that in looking at the Constitution, to his distress, he had found some inner contradictions, and that he could show how in a perfectly legal manner it would be possible for somebody to become a dictator and set up a Fascist regime, never intended by those who drew up the Constitution.”

With him to the citizenship hearing he asked his two closest friends, Einstein and Morgenstern. His examiner was Judge Phillip Forman. As Morgenstern later recalled in a draft of a Memorandum from Mathematica entitled History of the Naturalization of Kurt Gödel (dated September 13th 1971):

Examiner: "Now, Mr. Gödel, where do you come from?"

Gödel: "Where I come from? Austria."

Examiner: "What kind of government did you have in Austria?"

Gödel: "It was a republic, but the constitution was such that it finally was changed into a dictatorship."

Examiner: "Oh! This is very bad. This could not happen in this country."

Gödel: "Oh, yes. I can prove it."

As Morgenstern writes, “Einstein and I were horrified during this exchange; The examinor was intelligent enough to quickly quieten Gödel and say “Oh god, let’s not go into this” and broke off the examination at this point, greatly to our relief”. Morgenstern’s notes from the day are included below:

Gödel’s Loophole

“One of the great unsolved problems of constitutional law” — John Nowak

Could a technical loophole in the constitution ever allow a dictatorial regime to emerge in the United States? Legal scholar F.E. Guerra-Pujol argues that if so, Gödel’s objection was likely with the “amending power in Article V, and so the logical possibility of “self-amendment”. His conjecture appears in the paper

- Guerra-Pujol, F.E. (2012). Gödel’s Loophole. Capital University Law Review 41, pp. 637–673.

Article V

Guerra-Pujol (2012) argues that the “design defect” Gödel observed in the United States Constitution likely related to Article V, which describes the “process whereby the Constitution, the nation’s frame of government, may be altered.” The article in other words allows the people to change or amend the Constitution through a two-stage amendment process, which requires:

Article V Process of Amending the United States ConstitutionStage 1

A 2/3 majority approval by the House of Representatives

A 2/3 majority approval by the SenateStage 2

A 3/4 majority by the States

Crucially however, as Guerra-Pujol (2012) points out, although changes to the constitution through this process would be incredibly difficult to pass:

Article V does not prevent any change or amendment to Article V itself.

Was this Gödel’s observation which in theory might allow for a dictatorship to emerge in the future? If so, the weakness Gödel observed is the following:

If the procedural requirements of Article V may be amended, they may be amended "downward", that is, reduced or eliminated, making it easier to amend the Constitution in the future.- Excerpt, Gödel's Loophole by F.E. Guerra-Pujol (2012)

This, in turn, may over time increase the probability of a future amendment that allows for the emergence of a constitutional dictatorship.

After the Hearing

As Morgenstern writes in his memorandum, after the hearing: “We left, drove back to Princeton, and as we came to the corner of Mercer Street, I asked Einstein whether he wanted to go to the Institute or home. He said, “Take me home, my work is not worth anything anyway anymore”. […] Then off to Einstein’s home again”.

As they reached Einstein’s home, the great man turned back toward Gödel and said:

Einstein: “Now Gödel, this was your one but last examination”

Gödel: “Goodness, is there still another one to come?”

Einstein: “The next examination is when you step into your grave.”

Gödel: “But Einstein, I don’t step into my grave”

Einstein: “That’s just the joke of it!”

A genius of relativity but perhaps not of comedy, that Einstein.

“With that he departed. I drove Gödel home. Everybody was relieved that this formidable affair was over: Gödel had his head free again to go about problems of philosophy and logic”. — Oskar Morgenstern