Famous Diophantine Equations

A Diophantine equation is an algebraic equation with several unknowns and integer coefficients

D

iophantine equations have been in the news lately. This because, on September 6th 2019 a team lead by researchers at the University of Bristol and MIT announced that they had discovered the final solution to the so-called “sums of three cubes” problem, which asks for integer solutions to the equation x³ + y³ + z³ = k for values of k between 1 and 100. Since its formulation in 1954 at the University of Cambridge, up until 2016, every solution had been found except two, for k=33 and k=42. In March of this year, mathematician Andrew R. Booker in a paper published on arXiv.org announced that he had found the correct solution for k=33 using weeks of computation time on Bristol’s supercomputer. His solution, presented in the paper “Cracking the problem with 33” is:

Then, just a week or so ago, again the news broke: k=42 had been discovered, again by Booker along with another Andrew, Andrew Sutherland at MIT, using the crowd-sourced so-called Charity Engine. Their answer is:

For values of k between 1 and 1000, solutions still remain to be found for the integers 114, 165, 390, 579, 627, 633, 732, 906, 921 and 975.

Diophantine equations

The sums of three cubes problem is an example of a problem asking for solutions to a Diophantine equation, which may be defined as:

Definition

A Diophantine equation is an algebraic equation with several unknowns and integer coefficients.

That is, Diophantine equations are equations featuring several unknown variables (x,y, z, ..) whose solutions (=0) only appear when the coefficients of the equation (a, b, c, …) are integers ( … ,-2, -1, 0, 1, 2, … ).

The Linear Diophantine Equation

A linear Diophantine equation is an equation of the first-degree whose solutions are restricted to integers. The prototypical linear Diophantine equation is:

where a, b and c are integer coefficients and x and y are variables. Typical linear Diophantine problems hence involve whole amounts, such as e.g (Brilliant.org, 2019):

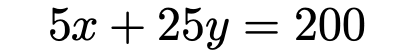

How many ways are there to make $2.00 from only nickels and quarters?

The solutions to the problem are found by assigning variables to the number of nickels (x) and the number of quarters (y). We know that $2 is 200 cents (c), and that a nickel is worth 5 cents (a) and a quarter 25 cents (b). Thus, we easily arrive at the equation specifying the number of ways in which we can have $2.00 in nickels and quarters:

Now, because this is a single equation with two unknowns, we cannot solve for one variable at a time (as one could do with a typical system of linear equations). Instead, for the linear case, we can use the following theorem:

Linear Diophantine equations have integer solutions if and only if c is a multiple of the greatest common divisor of a and b.If integers (x, y) constitute a solution to the linear Diophantine equation for given a, b and c, then the other solutions have the form (x + kv, y - ku) where k is an arbitrary integer and u and v are the quotients of a and b (respectively) by the greatest common divisors of a and b.

The greatest common divisor (GCD) of two or more integers, which are not all zero, is the largest positive integer that divides each of the integers. For our example above, we can begin by factoring out the common divisor 5, obtaining:

The greatest common divisor of a and b, 1 and 5, is 1. Any non-negative c is a multiple of 1. There are nine such multiples of 5 which are less than or equal to 40. They are 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40. Therefore, there are nine ways to make $2.00 from nickels and quarters. They are:

(0, 8), (5, 7), (10, 6), (15, 5), (20, 4), (25, 3), (30, 2), (35, 1) og (40, 0).

The above process is a simple version of what is called Diophantine analysis, the process required for finding solutions to Diophantine equations. The questions typically asked during such analyses are:

- Are there any solutions?

- Are there any solutions beyond some that are easily found by inspection?

- Are there finitely or infinitely many solutions?

- Can all solutions be found, in theory?

- Can one in practice compute a full list of solutions?

Popular techniques used to solve Diophantine equations include factor decomposition, bounding by inequalities, parametrization, modular arithmetic, induction, Fermat’s infinite descent, reduction to Pell’s and continued fractions, positional numeral systems and elliptic curves (Wikiversity, 2019).

The Hardy-Ramanujan Equation

The Hardy-Ramanujan number 1729, known as a “taxi cab number” is defined as “the smallest number expressible as the sum of two cubes in two different ways”, from an anecdote of the British mathematician G. H. Hardy when he visited Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan in the hospital:

“I remember once going to see him when he was ill at Putney. I had ridden in taxi cab number 1729 and remarked that the number seemed to me rather a dull one, and that I hoped it was not an unfavorable omen. “No,” Ramanujan replied, “it is a very interesting number; it is the smallest number expressible as the sum of two cubes in two different ways.” — G.H. Hardy (1918)

The equation at the heart of taxicab numbers is Diophantine, namely the equation:

The two different ways 1729 is expressible as the sum of two cubes are 1³ + 12³ and 9³ + 10³. So far, six taxicab numbers are known. They are:

Ta(1) = 2

= 1³ + 1³

Ta(2) = 1,729

= 1³ + 12³ = 9³ + 10³

Ta(3) = 87,539,319

= 167³ + 436³ = 228³ + 423³ = 255³ + 414³

Ta(4) = 6,963,472,309,248

= 2421³ + 19083³ = 5436³ + 18948³ = 10200³ + 18072³ = 13322³ + 16630³

Ta(5) = 48,988,659,276,962,496

= 38787³ + 365757³ = 107839³ + 362753³ = 205292³ + 342952³ = 221424³ + 336588³ =231518³ + 331954³

Ta(6) = 24,153,319,581,254,312,065,344

= 582162³ + 28906206³ = 3064173³ + 28894803³ = 8519281³ + 28657487³ = 16218068³ + 27093208³ = 17492496³ + 26590452³ = 18289922³ + 26224366³

Fermat’s Last Theorem

Numbers expressible as the sum of cubes (such as those from the sum of three cubes problem and the Hardy-Ramanujan number) were first mentioned in 1657 by Bernard Frénicle de Bessy, who described the property citing the example of the number 1729 in his correspondences with John Wallis and Pierre de Fermat. Fermat’s name since has become somewhat synonymous with the more general case of the problem, following his 1637 assertion in the margin of a copy of Diophantus’ Arithmetica that no three positive integers a, b, and c satisfy the Diophantine equation

Which Fermat (in)famously stated that he had proven to be true for integer values of n larger than 2, but which he could not include in his notes in the book because the margin was too narrow:

Cubum autem in duos cubos, aut quadrato-quadratum in duos quadrato-quadratos, et generaliter nullam in infinitum ultra quadratum potestatem in duos eiusdem nominis fas est dividere cuius rei demonstrationem mirabilem sane detexi. Hanc marginis exiguitas non caperet - Pierre de Fermat, 1637

Translated, his text reads “It is impossible for a cube to be the sum of two cubes, a fourth power to be the sum of two fourth powers, or in general for any number that is a power greater than the second to be the sum of two like powers. I have discovered a truly marvellous demonstration of this proposition that this margin is too narrow to contain.” (Nagell, 1951).

The conjecture was famously finally proven after 358 years in 1994 by English mathematician Andrew Wiles in his paper Modular elliptic curves and Fermat’s Last Theorem published in the Annals of Mathematics 141 (3), pp 443–551. Wiles’ proof by contradiction, at 129 pages long, uses techniques from algebraic geometry and number theory to prove a special case of the modularity theoremfor elliptic curves, which together with Ribet’s theorem implies the truth of Fermat’s Last theorem. Due to its extensive use of modern mathematics, it is certain that Wiles’ proof cannot be the same claimed to be found by Fermat — which still remains lost (and likely wasn’t a proof at all).

Pythagorean triples

The perhaps most well known Diophantine equation of all is a particular case of the equation from Fermat’s Last Theorem, but for n=2. This is the equation which helps one find the length of the sides of a right angled triangle

Pell’s Equation

Pell’s equation (sometimes the Pell-Fermat equation) is any equation of the following form where n is a given positive square-free integer and integer solutions are sought for x and y:

This Diophantine equation was first studied extensively by Indian mathematician Brahmagupta around the year 628. He developed the so-called chakravala method for solving it and other indeterminate equations. This about a thousand years before its namesake, English mathematician John Pell (1611–1685) studied it while working under Johann Heinrich Rahn. Its name arose from a mistaken attribution of a solution provided by Lord Brouncker to Pell by Leonard Euler in 1732–33.

Equations of the form of Pell’s equation with n = 2 are known to have been studied as early as 400 BC in both India and Greece, in addition to the case where x² − 2y² = −1, because of the connection of these two equations to the irrational number obtained from calculating the square root of 2 (if x and y are positive integers satisfying this equation, then x/y is an approximation of √2).

In Cartesian coordinates, the equation has the form of a hyperbola, as solutions to the equation occur wherever the curve passes through a point whose x and y coordinates are both integers, such as x = 1, y = 0 and x = -1, y = 0. Lagrange proved that as long as n is not a perfect square, Pell’s equation has infinitely many distinct integer solutions.

The Erdős–Straus Conjecture

The Erdős–Straus conjecture states that for every integer larger than 2, the rational number 4/n can be expressed as the sum of three positive unit fractions. That is, for every integer n ≥ 2, there exists positive integers x,y and z such that:

If n is a composite number (n = pq), then an expansion for 4/n could be found from an expansion of either 4/p or 4/q. Thus, if a counterexample exists, the smallest n forming a counterexample would have to be a prime number. This result be further restricted to one of six infinite arithmetic progressions modulo 840 (Mordell, 1967).

The conjecture is named after mathematicians Paul Erdős and Ernst G. Straus who formulated it in 1948. It remains unproven as of 2019. The Diophantine version of the equation appears when one multiplies by the denominator on both sides and obtains its polynomial form:

For n=5 for instance, there are two solutions:

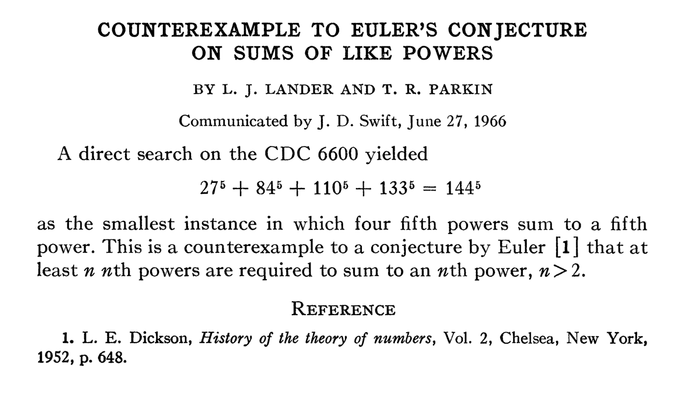

Euler’s Sum of Powers Conjecture

Leonard Euler in 1769 incorrectly conjectured that Diophantine equations of the form

That is,

Euler's sum of powers conjecture

For all integers n and k greater than 1, if the sum of the n kth powers of positive integers is itself a kth power, then n is greater than or equal to k.

That is, that if the sum of the first n terms of aᵏ is equal to a term that is itself a kth power (e.g. bᵏ), then n must be greater than or equal to k. The conjecture was an attempt by Euler to generalize Fermat’s last theorem. The conjecture was disproven in 1966 by Lander and Parkin through computer search, when they discovered a counterexample for the case k=5, announced in the so-called “shortest paper ever published”:

The special case of k = 4 was later disproved by Elkies (1986) who discovered a method of constructing infinite series of counterexamples. His smallest counterexample was:

2,682,440⁴ + 15,365,639⁴ + 18,796,760⁴ = 20615,673⁴

This was later improved by Roger Frye (1988) who, using computer search, found that the smallest possible counterexample is:

95,800⁴ + 217,519⁴ + 414,560⁴ = 422,481⁴

History

The first known study of Diophantine equations was by its namesake Diophantus of Alexandria, a 3rd century mathematician who also introduced symbolisms into algebra. He was author of a series of books called Arithmetica, many of which are now lost.

Hilbert’s Tenth Problem

Hilbert’s 10th problem asked if an algorithm existed for determining whether an arbitrary Diophantine equation has a solution. The problem was stated by David Hilbert in 1900 as part of his list of 23 open problems in mathematics. Hilbert’s original formulation was as follows:

Hilbert's Tenth Problem

Given a Diophantine equation with any number of unknown quantities and with rational integral numerical coefficients: To devise a process according to which it can be determined in a finite number of operations whether the equation is solvable in rational integers.

The problem was solved in 1970 by Yuri Matiyasevich who in his doctoral dissertation proved that a general algorithm for solving all Diophantine equations cannot exist. His solution, which implies the unsolvability of Hilbert’s Tenth Problem, asserts that the class of Diophantine sets is identical with the class of recursively enumerable sets (Matiyasevich, 1993).

In modern terminology, Hilbert’s Tenth Problem is hence an undecidable problem. That is, it is a decision problem for which it is proved to be impossible to construct an algorithm that always leads to a correct yes-or-no answer.